In August 2018, Leeds medics Rachel, Alice, Heather and Katie spent their medical elective period at the LED Health Post in Quisuar, in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca. During their four weeks they also ran mobile clinics in surrounding villages, delivering school supplies en route. Here’s their report.

Elective Report

Over the summer of 2018 we as four 4th year medical students spent our medical elective period at the health post in Quishuar, a remote village situated in the Cordillera Blanca mountain region of Peru. The team consisted of ourselves, Tula a permanent nurse at the post and Juan, an interpreter and guide. The health post aims to provide basic healthcare to the 75 families of Quishuar and sometimes to surrounding villages at a reasonable cost of 5 soles per consultation. We aimed to contribute to the running of the health post, promote health education and also teach English to the local children.

Fundraising

Before departing for Quishuar, we raised funds to allow us to purchase some resources to contribute as well as donate to the charity that is responsible for building and supporting the sustainability of the post, Light Education Development (LED). LED aims to provide sustainable solar lighting, basic education and fundamental healthcare to remote communities in the developing world. We were inspired to start this following the walk to Dufton Pike in May 2018 where we met many of the people involved with the charity. We thoroughly enjoyed the day and saw first hand the commitment to the cause from so many people which was inspiring.

What makes Quishuar unique?

We found the Quishuar population had an inflated view of medical management, almost always preferring tablets over conservative or surgical management. We thought this may be due to a combination of lack of education surrounding common health problems and accessibility to alternative means of treatment, being so far away from a hospital (12 hours by car and significant expense) or other supportive services.

In terms of clinical practice, there were several differences to note that became apparent whilst working alongside Tula. This was most obvious with regards to the management of infections; we would often think that antibiotics were unnecessary, but it seemed the norm to readily give out antibiotics even when there was little evidence of infection. This was difficult to negotiate at times due to differing opinions as to what the problem was as well as the language barrier. Our antibiotic stewardship awareness is evident as we were much more cautious, however this may be less appropriate within a community where antibiotics are not so readily available and therefore resistance is far less likely.

Furthermore, there was an issue with non-returning for follow-up. It was unclear as to the main reasons for this, but we found that the knowledge that people are unlikely to return resulted in a change in our management, often distributing more medications at once and giving more long-term explanations of advice in order to pre-empt this problem.

Common presentations

One of the main problems was chronic dehydration, commonly manifesting as headaches and in many women, “urinary tract infection” symptoms. When asked, most people reported drinking only a glass or two of water a day and there was little understanding of the relationship between poor hydration and kidney problems/headaches. We tried to make the most of this situation, taking the time to explain this to patients during consultations. The language barrier made this challenging at times, with the level of patient understanding difficult to gauge but we got into a habit of asking every patient about drinking habits and advising them to drink 2L of water per day.

Giardia and worms were the two most common gastrointestinal presentations seen; often entire families came in with the same symptoms. We had a low threshold for treating these conditions as we had been advised they were common and recurrent, and quickly treated with a short course of medication. Hand hygiene was an important topic to raise here, as most people worked in agriculture and kept animals in and around the house, a major source of these infections.

A condition that we found particularly shocking was “pterygium” an ocular condition caused by sun damage. Therefore, one of our main education drives was sun protection; encouraging people to wear their hats low over their face and to purchase sunglasses if they could. A recommendation for future groups would be to collect sunglasses and provide them to the community to provide protection to as many people as possible.

Additionally, we saw several people with permanently scarred corneas as a result of untreated corneal ulcers. A case that was particularly upsetting was a young man who presented with a frank cornel scar, hoping for his longstanding blindness to be cured. His expectations were so far removed from what was possible making it a difficult conversation to have, especially as he was insistent on receiving medications to cure his condition. The frustration was only heightened due to the preventability of his condition. Whilst a corneal transplant was discussed (the only curative treatment here), it would never be possible for this patient to explore the options due to his financial position which was difficult to accept having only experienced the free services offered by the NHS in the UK.

Education

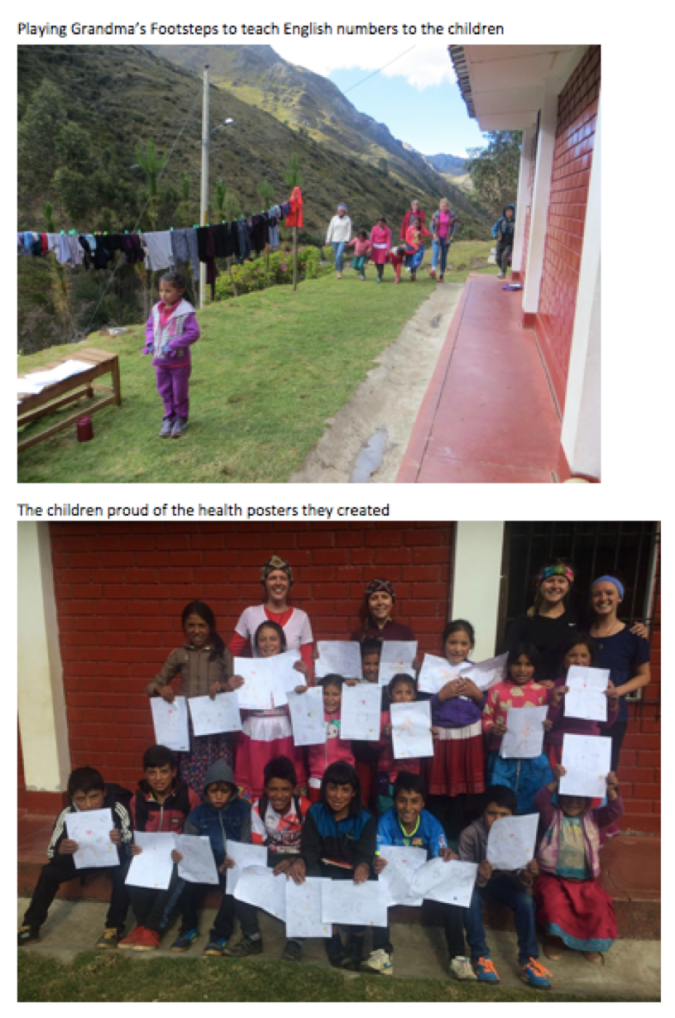

During our time, we had the opportunity to teach local children English in our afternoons. These sessions were well attended and we worked through different themes such as: weather, food and sports. The children were enthusiastic to learn and a joy to teach. Some would travel from neighbouring villages and all would work hard – even after a full day at their schools! On our last day we organised a mini-Olympics which was well received and got every child equally involved as they practiced their English through team sports. All the work that the children completed was handed out to them with a certificate, which we hope will keep them motivated to continue to work hard. We also taught about health education, the key topics being sanitation, signs of infection and when a doctor is required. We believe that this along with the water advice is invaluable to the community and it was great to take the opportunity to organise this. Another session we managed to organise was sex education with 20 attendees, aged between 14-17. This session was held with the help of Juan and lots of questions were asked at the end, demonstrating the engagement and interest in the topic. We hope there is scope for it to become a yearly event to help tackle high rates of teenage pregnancy and STIs. Our

Reflections

We can safely say that this was a unique and unforgettable experience on so many levels; both from a medical and personal perspective. From our dancing welcome party to our first taste of guinea pig we had so many new experiences in such a different environment and we all felt that we improved our medical skills as well as our Spanish speaking skills. The health post is evidently a very highly regarded epicentre in the village that contributes not only medically but also socially to the people of Quishuar.

A few highlights

Interested in volunteering with us in Peru or Nepal? Use the Contact LED form on www.lighteducationdevelopment.org or message us on facebook.com/LEDCharity to find out about opportunities in 2019.