In summer 2022, Leeds medics James Peaty and George Thomas spent their medical elective period at the health post LED supports in Quisuar, in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca. As well as providing healthcare from the clinic in Quishuar and undertaking home visits for local elderly people who weren’t able to come to the clinic, James and George also ran a mobile eye clinic to distribute reading and distance glasses away from Quishuar and provided English lessons for local children in Quishuar. Here’s James’ report.

Aims and objectives

The key aims of the elective were to:

- Experience healthcare provision in a developing country.

- Experience healthcare provision by an international charity.

- Contribute to healthcare provision in an area of need by fundraising for and purchasing a laptop as well as transporting glasses donated in the UK to be handed out on arrival.

- Learn a new language using audiobooks and Duolingo.

- Conduct English lessons for local school children.

Background and Organisation

I first heard about the elective form a friend, Hugh Harris, 3 years above me on the MBChB program at Leeds. He along with 3 other University of Leeds Medical Students had volunteered at the clinic based in the village of Quishuar in 2019. Through Hugh I was able to contact Val Pitkethly, the founder of the charity, Light, Education, Development (LED), that supports the clinic. After a short application process that involved submitting a CV and meeting with Val to discuss practicalities and get more information my elective partner, George Thomas, and I were accepted onto the elective.

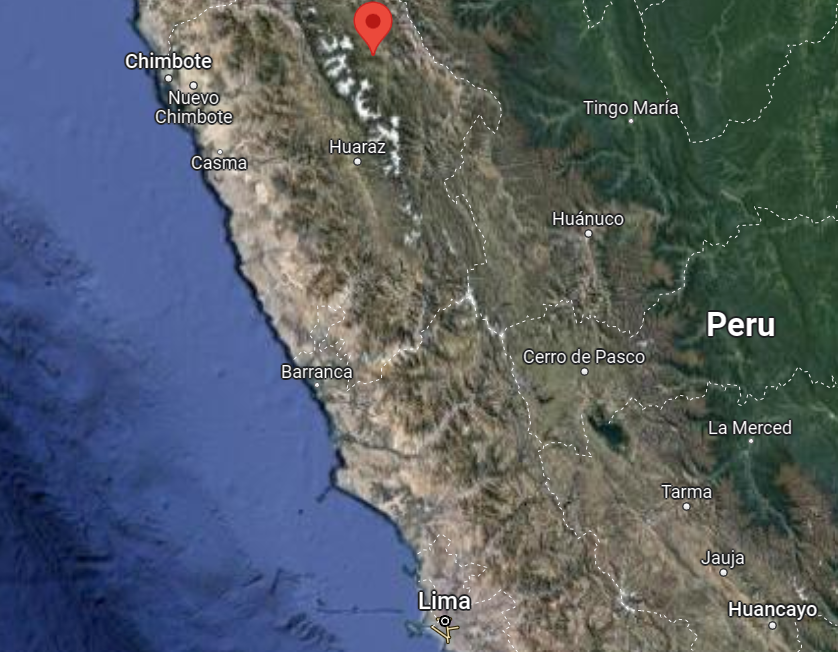

The clinic itself is based in a mountain village on the eastern side of the Cordillera Blanca range in central Peru. It serves the people who live at the highest elevation at the western end of the province of Lucma who are furthest from the government run clinics that sit on either side of the range.

The main activity undertaken by the population served by the clinic appeared to be small scale farming and labouring jobs and the main form of housing was mud brick houses.

The clinic building consists of 4 rooms; the kitchen and nurse’s quarters, a waiting room, the consulting room and the bedroom. Running of the clinic is funded by the charitable donations mainly form the UK but also worldwide thanks, in part, to an international network built through Val’s mountain guiding clients.

There is a permanent Peruvian nurse stationed there throughout the year but all other medical staff are volunteers. Volunteers were mainly doctors and 5th year medical students from the UK but doctors from other developed nations had also staffed the clinic on a temporary basis in the past.

Type of work performed

The clinic functioned as a basic source of primary care. To fulfil this function the clinic was equipped with basic examination equipment including all the equipment necessary to perform observations, a few books including the BNF and Oxford handbook of clinical medicine and a large stock of various basic medications ranging from antimicrobial agents to proton pump inhibitors.

In the clinic our history taking, and examination skills were well practiced. Diagnosis based exclusively on these was essential as the only tests we had access to were urine dipsticks. Communication skills were also tested as none of the patients spoke English and many did not speak Spanish but instead only the Incan language of Quechua. Thus, all communication had to go through the translator working with us.

Other functions that were performed by the clinic included: distribution of glasses, English lessons for local children and home visits for local elderly people who weren’t able to come to the clinic. My elective partner and I were involved in all these functions. For example, one weekend we packed up enough for an overnight camping trip and drove across to an adjacent valley, hiked up to a village with no road access and set up a field clinic distributing glasses to the anyone who required them.

I had bought the glasses, which included both reading and distance prescriptions labelled as various strengths, in a shoe box from the UK. In the box there was also included a Snellen chart and reading materials of different sizes to help us determine, using a bit of trial and error, what strength of glasses each patient required. Over thirty people turned up to this mobile glasses clinic in both the evening and the morning of the next day. In the end we ran out of distance glasses.

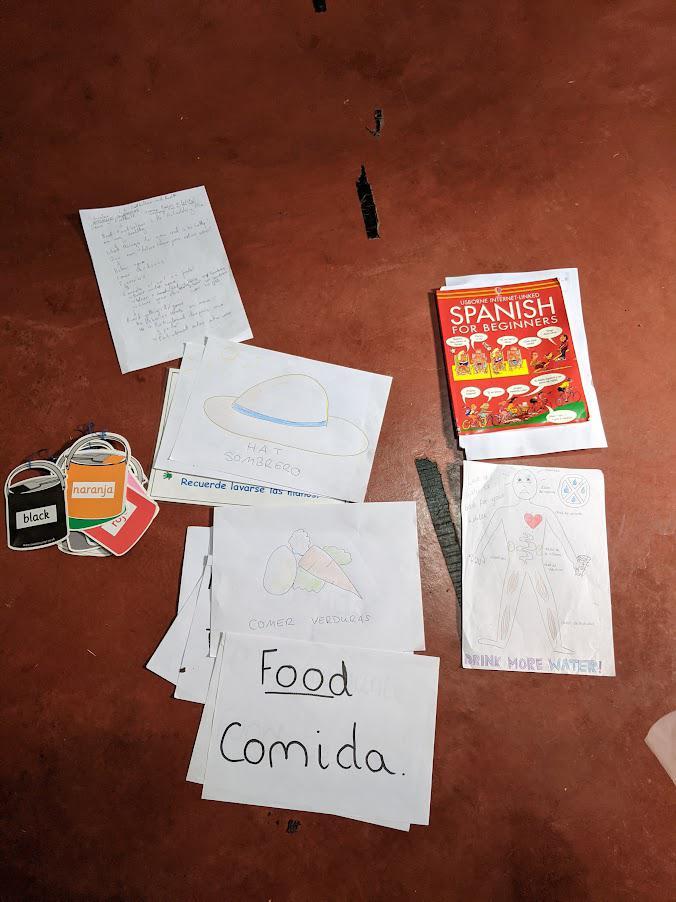

English lessons were conducted after the children had finished school 3 days a week. We taught a small group of keen, primary school age, students basic things like the colours, animals, how to say their name and types of food in English. We also included games, songs (such as head, shoulders, knees and toes) and education about basic hygiene, sun safety and healthy eating. We tried to use as many visual aids as possible and to work form a rough plan.

Other tasks we performed while at the clinic included taking stock of and helping order medications, alphabetising medications, taking stock of equipment and helping purchase or replace equipment. We also helped purchase and set a laptop for the clinic that we had fundraised for by running the Leeds Half marathon.

Case report

During the elective I was fortunate enough to be exposed to clinical cases that were fundamentally different from cases I commonly saw in general practice in the UK. An example of this was a 5-year-old child bought in by his mother due to a month-long history of gradually worsening diarrhea and epigastric pain particularly after eating. He had also developed a chronic cough in the last month. On further questioning it was noted that because of the stomach pain the child wasn’t eating as much as normal. The key positive finding on examination was that the boy was underweight for his height and age measuring at the 50th centile in height for his age but only at the 2nd centile for weight.

On discussing my findings, I was told that this was a classic presentation of worms. One study done on the prevalence of parasites in rural Peru found that half of the participants (aged 3 and above) had at least one intestinal helminth or protozoan detected by microscopy. The most common parasite detected was Strongyloides stercoralis which infected 24.5% of the population studied. This nematode can produce symptoms of pneumonitis, chronic malabsorption, diarrhea and abdominal pain thus accounting for the child’s presentation.

I was informed that the standard treatment for this infection was Albendazole. Although the Oxford handbook of clinical medicine recommended Ivermectin as the first line treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis without access to stool microscopy or blood tests it was impossible to be sure of the causative organism. Albendazole has been shown to have good efficacy against a range of roundworms including others common to rural Peruvian populations like hookworm. So, using this broad-spectrum drug was more likely to be effective in treating this child.

In addition to pharmaceutical management, I learnt that it is important to educate patients on basic hygiene and protective measures to avoid re-infection. Many parasites are picked up by the faecal oral route but hookworms and Strongyloides stercoralis can also burrow through the skin. Studies have shown that those who do not wear shoes when leaving the house, and particularly when defecating are more likely to become infected with Strongyloides stercoralis. Therefore, education about regular handwashing is highly important but shoe wearing is also likely to reduce rates of nematode infection. However, this is easier said than done in an area where houses have dirt floors and there is poor access to proper sanitary facilities. Living in close proximity to parasite carrying livestock may also increase risk of infection.

Extra curricula activities

During my elective I was able to significantly improve my Spanish through a combination of immersion, Paul Noble audiobooks and the Duolingo app which I had been using to practice daily since January 2022.

Conclusion

Overall, I believe the elective met almost all of my aims. I was able to fully experience what it is like to work in an international charity and to contribute to healthcare provision in an area of need by: fundraising for, helping purchase and set up a laptop for the clinic; taking and handing out glasses donated in the UK to those who cannot afford them; and helping with the day to day running of the clinic. Furthermore, I significantly improved my understanding of Spanish and taught English to local primary school aged children.

I would have liked to experience the Government run hospitals and clinics to get a full experience of how their health system works. Although this was originally planned it did not end up coming to fruition.

Additionally, this elective had many learning points. These included: learning about diseases, like parasitic worms, that I hadn’t come across in the UK; learning what it means to live in a developing nation and how health needs in a developing nation are different from those of developed nations such as the UK; and the practicalities of healthcare provision in a resource poor environment.